Like a phoenix rising from its ashes, European countries wanted to chart an entirely new direction after the devastations of WWII. Perhaps, the people of this region wanted to relive the era of Charlemagne, but more peacefully.

So, the first glimpse of the European Union (EU) appeared with the signing of the Dunkirk Treaty in 1947 between France and Britain. But it was not until the ratification of the Single European Act (SEA) on February 28, 1986, that the shift towards a single currency materialized.

Almost 13 years after SEA, the euro became the official currency for accounting and electronic payments within the EU. On January 1, 2002, the European Central Bank started distributing banknotes and coins, making the euro the bloc’s official currency. Interestingly, the new money would not substitute the British pound.

“Five tests and a funeral”

The first signs of doubt concerning the UK’s willingness to join the eurozone – countries that adopted the euro – became crystal clear. On October 27, 1997, the Chancellor of the Exchequer described the UK government’s position on the impending Economic and Monetary Union (EMU).

Speaking before the House of Commons, Gordon Brown, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, said that the UK was not ready to pool economic sovereignty with EU member states as a matter of principle.

But Mr. Brown recognized that addressing the question of a common currency from the perspective of principle would, eventually, lead to capitulation to the EMU. On the question of principle, Mr. Brown said, amid a rapturous House of Commons, the government believes the UK should adopt the euro if the single currency ends up being successful.

Nevertheless, the British government outlined five economic tests to evaluate the case for adopting the common currency. According to Mr. Brown, the tests were critical to protecting the businesses and livelihoods in the UK.

The tests covered the UK economy’s main areas, including economic cycles, flexibility, investment, financial services, and employment. On economic cycles, Gordon Brown argued that adopting the euro would become possible only when the UK’s business cycle converges with that of the eurozone.

Because of the impossibility of the tests, the May 3, 2003 edition of The Economist described the chances of the UK joining the EMU as “five tests and a funeral.” According to the magazine, the case for adopting the euro failed four of the five tests by 2005.

The UK economy is healthier than the eurozone

One of the five tests outlined in 1997 was jobs and growth of employment. The government argued that it would be reasonable to join the monetary union if there was an insignificant disparity between the average unemployment rate in the EU and the UK.

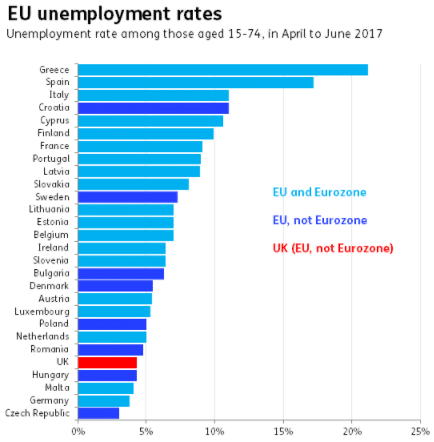

On this count, the EU fails hopelessly. As of 2017, the average unemployment rate in the eurozone was 9.1%, against 4.4% for the UK. Only four European countries performed better than Britain, and only two of them were eurozone members.

After the Great Recession, the eurozone entered a debt crisis. Close to five countries suffered devastating economic consequences, and the whole monetary union was forced into austerity. For this reason, the bloc experienced the most protracted economic stagnation compared to other developed economies.

On the other hand, the UK’s monetary sovereignty enabled the central bank to take necessary steps to cushion its economy from disaster. For example, the Bank of England depreciated the pound and loosened the monetary policy to make its exports more competitive.

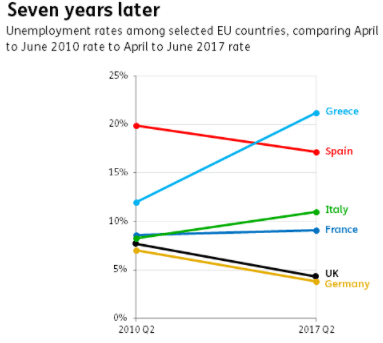

The eurozone’s unemployment crisis is deepening with time. Over the seven years between 2010 and 2017, unemployment rates increased among most of the major eurozone economies. Only Germany was able to record a different result – see the figure above.

Certainty in the bond market

The global bond market is an essential source of financing for government projects worldwide. Without stable and reliable access to the market, many governments would not deliver crucial projects, let alone function properly. For context, the global bond market was worth $128.3 trillion as of August 2020, and government-related bonds accounted for 68% of the total.

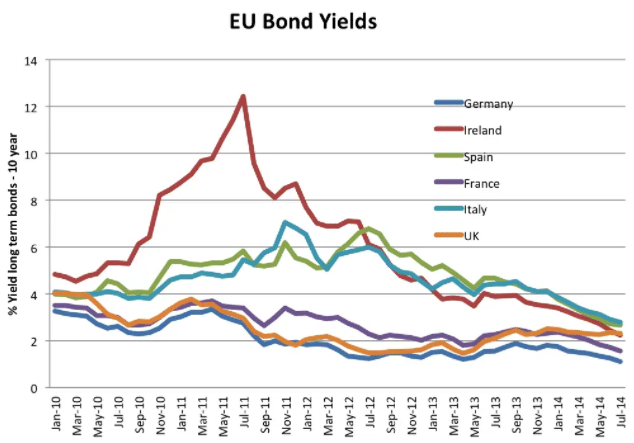

From the preceding, the UK government feared the worst happening to its economy if it lost the ability to stabilize the domestic bond market. For instance, the Bank of England wanted to retain the status of the lender of last resort instead of relying on the ECB. This way, the BoE would buy bonds to offset temporary shortfalls and implement radical monetary policies such as quantitative easing to prevent a debilitating recession.

Fortunately, this arrangement saved the UK bond market in the aftermath of the Great Recession. While bond yields skyrocketed in the eurozone in 2011-2012, the UK’s bond market was relatively calm.

Brexit happened

The June 2016 plebiscite was the final nail on the euro’s coffin in the UK. On the 23rd of the month, the people voted to allow the UK government to initiate the exit from the EU. The current Prime Minister had promised to resign if the proponents prevailed, which he did moments after the final vote was counted.

Since the euro came into effect, Britain had been operating as an integral part of the eurozone without being confined to the common currency. After Brexit, even the borders between the EU and the UK would no longer be open. The movement of labor and trade would now be subject to border controls and tariffs.

Bottom line

In early 2020, the curtain closed on the EU project as envisioned by the Anglo-French Dunkirk Treaty. Also, the EU-UK agreement meant that the prospects of the UK ever adopting the euro were dead and gone.

Nevertheless, it will take decades to extricate the two economies completely. One has to recall that the UK and the larger Europe have a long history of marriage and divorce. The region was one big nation during the era of the Frankish Kingdom. Therefore, one cannot rule out the possibility of the UK coming back into the fold and perhaps shrugging off the sterling pound for good.