One of the most common pieces of advice these days in the financial world has been “Do not fight the central bank.” Central banks across the world and especially in the developed nations, have been pivotal in rescuing economies and markets. In times of economic distress, central banks have used every arrow in their quiver, from low interest rates to quantitative easing to yield curve control in order to support the economy. In fact, ‘Bernanke Put’ was a term coined specifically because of Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke’s actions. Whenever the markets would falter, the Fed would step in and rescue them, thus putting a floor on the prices similar to what a put option does in a portfolio.

So whenever traders or investors try to go short on any asset based on economic fundamentals, they are in for a rude shock. Even though their trade makes perfect sense, it more often than not results in losses as the central banks artificially distort market prices. This just goes on to show how incredibly powerful central banks are. Even large institutions like investment banks and pension funds have booked millions of dollars in losses trying to bet against the actions of central banks.

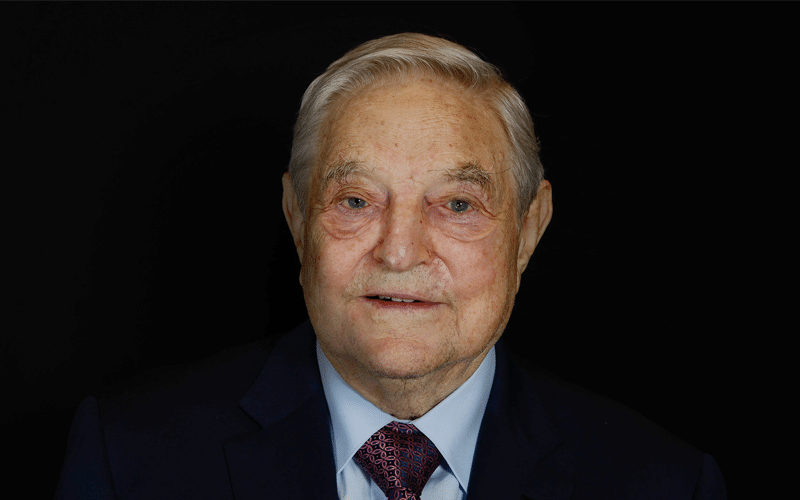

However, in September 1992, one trader, beyond all odds, managed to bring the mighty Bank of England to its knees, his name is George Soros.

Who is George Soros?

George Soros is a fund manager, and in his career spanning over several decades, he has successfully run several hedge funds. In the 1980s, he was running a fund called Quantum fund with several million dollars in assets. He often used derivatives to leverage his position. So even with several million dollars in assets, he used to take bets amounting to billions of dollars.

ERM and the Deutsche Mark peg

The European Exchange Rate Mechanism was set up in order to increase better coordination among the European economies. While Britain did not officially join the EERM, it adopted a policy that shadowed the Deutsche Mark, which was Germany’s currency. Germany in the 1980s was among the strong European economies, and tagging the Mark would mean having a stable currency.

In October 1990, the Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher decided to enter the GBP into a peg with the mark at the exchange rate of 2.95 DM to 1 GBP, thus becoming a part of the ERM. There was a 6% band within which GBP was allowed to deviate from the fixed 2.95 DM. If the GBP depreciated below the bottom of the range, which was DM 2.773, the government would intervene and purchase GBP in order to support the currency.

Now, in theory, this looked okay, but there were obvious problems with this. The British and German economies were vastly different. From 1990 Germany started raising interest rates in order to control the inflation arising out of Germany’s reunification. On the other hand, Britain was facing problems due to USD’s rapid depreciation. Many of Britain’s exports were in USD, and its depreciation meant that its exports became costlier and, as a result, less competitive.

So not only did GBP’s peg to the DM seem unsustainable, the British economy would, in fact, the benefit should the GBP slip below the lower bound permitted in the framework and depreciate significantly.

The Big Short

Many people in the market saw GBP’s exit from the peg as an inevitable outcome. However, the political climate at that time meant that defending GBP was a matter of national prestige. This meant that the British government would do everything in its power to stop the GBP from depreciating beyond the lower threshold.

There began a battle between the market forces and the British government. Obviously, betting against the government and the central bank is a risky business. In theory, they have unlimited resources and can manipulate market prices for extended periods of time.

However, George Soros was of the view that this was the time when the peg would break. From early 1992, Soros started increasing his short position on the sterling. He fundamentally believed that it was a wrong decision to bring in the GBP at the rate of 2.95 DM, which he deemed very high. So while the Bank of England kept buying the GBP in order to support the level, Soros kept on adding to his short position.

It was like an epic poker game where the last two on the table kept increasing their stakes, not really sure of the final outcome. One would walk out with massive gains, the other with massive losses.

It turned out that the British government and the Bank of England had completely misjudged both the economic outcomes of a DM peg and also their ability to defend that peg. Even massive purchases of GBP by the Bank of England stopped having any impact on the price. Finally, on 16th September 1992, they saw the writing on the wall and decided to withdraw GBP from the ERM.

The result was disastrous for the economy, and there was a massive movement across the financial markets. The day was infamously dubbed as the ‘Black Wednesday.’ But George Soros, who had quietly built up a $10 billion short position on the GBP, made $1 billion in profits. For this feat, he is also known as ‘The man who broke the Bank of England.’ The UK Treasury estimated its losses on that to be approximately GBP 3.14 billion.

It was one of the rare occasions where the collective strength of the government and the central bank was successfully challenged as they were in the end unable to defend GBP successfully.